Fraud is not merely a financial crime, but is a psychological phenomenon deeply rooted in human behavior. Understanding why individuals engage in fraudulent activities requires us to look beyond surface level greed or opportunity and explore the psychological processes that drive such actions. A fraudster’s psychology encompasses motivations, rationalizations, cognitive distortions, and behavioral patterns that enable them to deceive others while often justifying their actions internally.

Fraud, when seen through the lens by the examiners, it is often are perceived as financial or legal exercises, centered on tracing money trails, verifying documents, or enforcing regulations. However, beneath every fraudulent act lies a human mind making decisions, rationalizing behavior, and attempting to conceal the truth. For this reason, psychology plays a vital role in fraud investigations. From understanding the mindset of fraudsters to analyzing behavioral cues during interviews, the knowledge of psychology equips fraud examiners with sharper tools to detect, prevent, and resolve fraudulent activity. By studying the mindset of fraudsters, businesses, regulators, and society at large can better design preventive strategies and detect warning signs. Fraud is not confined to a particular class or culture. It occurs across industries, professions, and even within families. Hence, an exploration of the psychological underpinnings of fraudsters is essential in tackling the growing complexity of fraud in today’s world.

The psychology of a fraudster often begins with motivation. Unlike crimes of passion or impulse, fraud is typically calculated and deliberate. The motivations may include:

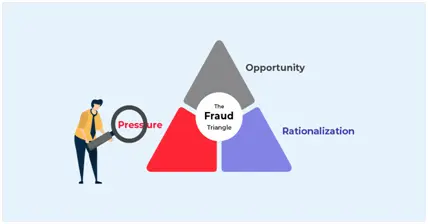

One of the most important frameworks to understand a fraudster’s psychology is the Fraud Triangle, which highlights three conditions that make fraud more likely:

Fraudsters rarely see themselves as criminals, instead, they rationalize actions through thoughts such as:

This rationalization reduces cognitive dissonance, enabling fraudsters to maintain a positive self-image while engaging in unethical conduct.

Fraudsters often use psychological defense mechanisms and distorted thinking to sustain fraudulent acts, which over time, become ingrained, making repeated frauds easier and reducing guilt.

Fraudsters often display recurring behavioral patterns that provide important clues for investigators. One of the most common is the use of charm and manipulation. Many fraudsters rely on charisma and persuasive tactics to lower suspicion and gain trust, making it difficult for colleagues or supervisors to question their actions. Alongside this, they often maintain excessive secrecy, closely guarding financial data, discouraging inquiries, and choosing to work in isolation to minimize the chances of detection. These behaviors create an environment where fraudulent acts can remain hidden for extended periods.

Another noticeable pattern is the tendency to live a lifestyle that is inconsistent with legitimate earnings. Living beyond means, such as sudden displays of wealth or unexplained luxury spending, is often a red flag. Fraudsters also exhibit overconfidence, believing strongly in their intelligence and ability to outsmart systems and controls, which can push them toward larger schemes. This mindset often blends with addictive risk-taking, where initial success in avoiding detection fuels greed and encourages escalation of fraudulent activities. Together, these patterns reflect not only the strategies fraudsters use but also the psychological traits that sustain their deception.

Not all fraudsters share the same mindset or approach. In fact, researchers have identified some broad psychological profiles that help us understand the diversity in fraudulent behavior. One such type is the Opportunist, who commits fraud when easy chances arise, often without long-term planning or elaborate schemes. These individuals may not set out with an intention to deceive, but the presence of weak controls or loopholes tempts them to act in the moment. In contrast, the Predator is far more calculated and dangerous. For this profile, fraud is not an accident but a way of life. Predators actively seek opportunities to exploit systems and people, often designing intricate methods to commit fraud repeatedly and on a larger scale. Unlike opportunists, they thrive on manipulation and deception as part of their lifestyle.

Further, the accidental fraudster, who is perhaps the most relatable profile. These are generally ordinary, law-abiding individuals who, under extreme pressure, be it financial hardship, family obligations, or workplace stress, succumb to fraudulent acts. Such behavior usually arises when combined with weak organizational controls that make fraud easier to execute. The accidental fraudster may not have engaged in such behavior if circumstances had been different. Taken together, these profiles highlight that fraudsters are not a homogeneous group but they can range from otherwise honest individuals pushed by circumstance to habitual manipulators who plan deception as a way of life.

The following case incidents that have taken place in the country over the past years further illustrate the psychological elements underlying these fraudulent practices:

Background: A man using the alias Dr. Rohit Oberoi (real name Abhishek Shukla), reportedly living abroad, created a fake matrimonial profile online. He befriended a woman in Pune, won her trust, promised marriage, and later engaged in fake business proposals involving associates in India & Singapore. Over time, convinced by these schemes, she transferred ₹3.6 crore.

If you analyse the psychological aspects behind the above case, one may be able to observe the following:

This case typifies how fraudsters leverage emotional vulnerability, promises and the rationalization to overcome victims’ suspicion. For a fraud examiner, noticing early red flags in these domains like requests for money, inconsistent stories, requests under emotional pressure are critical.

Case 2: Rose Valley Chit Fund Scam

Background: The Rose Valley Group ran large unauthorized collective investment / chit fund operations and Ponzi schemes, collecting large sums of money (over ₹15,000 crore) from depositors across multiple states in India.

Psychological elements involved:

In such mass frauds, psychological levers such as trust, social influence, greed, and authority are powerful. Fraud examiners need to understand how these levers are manipulated, and design controls, disclosures and investor education to reduce susceptibility.

Background: This was one of the largest corporate frauds in the country’s history, exposed in January 2009. Ramalinga Raju, the founder and chairman of Satyam Computer Services, admitted to manipulating the company’s accounts for several years by inflating revenues, overstating profits, and creating fictitious cash balances to project a stronger financial position than reality. This deception misled investors, regulators, and stakeholders, eroding trust in corporate governance in India. Mr. Raju justified the fraud as a way to maintain the company’s image and meet shareholder’s expectations, while believing he could continue the manipulation without being caught. The fraud grew in scale as small falsifications snowballed into massive discrepancies, ultimately leading to the collapse of investor confidence and the government’s intervention. The case highlighted how pressure, rationalization, and arrogance can drive even top corporate leaders to enact large scale fraud, reinforcing the need for stronger ethical practices and independent oversight in business.

This illustrates how psychological traits like hubris, fear of failure, loss of prestige, and pressure (from markets, from stakeholders) interplay. Fraud examiners must look not only at numbers but at the management culture, auditor independence, and the internal pressures leadership may face.

Case 4: Digital Arrest / Authority based Cyber Scams

Background: Scammers impersonate police, CBI, or other authority figures via video or calls, falsely accusing individuals of wrongdoing (e.g. drug trafficking), threatening arrest or legal consequences, sometimes showing fake documents, credentials, or evidence. Victims under threat transfer money, sometimes sizable amounts, in fear.

Psychological elements involved:

These cases underscore that sophistication in deception is often psychological rather than purely technical. Fraud examiners need to understand what makes victims deferential to authority, how fear works, and how those psychological levers can be used against people.

Understanding the psychology of fraudsters has several practical applications in preventing fraud. Strengthening internal controls helps reduce opportunities by ensuring proper checks, balances, and independent oversight. Promoting an ethical culture within the organization minimizes rationalizations by fostering integrity and rewarding honesty. Establishing whistleblower channels further reduces secrecy and empowers individuals to report suspicious behavior without fear. Additionally, providing training on behavioral red flags enables employees and auditors to recognize warning signs such as lavish lifestyles, defensiveness, or secrecy. By addressing these psychological factors, organizations can build stronger defenses against fraud.

Fraud is not simply an economic act but a psychological construct that blends motivation, opportunity, and rationalization. A fraudster’s psychology is shaped by their inner desires, cognitive distortions, and behavioral traits that allow them to deceive others while maintaining self-justification. Recognizing these mental processes is crucial not only for law enforcement and auditors but also for society at large to reduce the stigma of unpredictable crime and instead focus on prevention through understanding human behavior.

For fraud examiners, psychology is not an optional tool but an essential lens through which fraud must be understood. Numbers can be manipulated, but human behavior often exposes hidden truths. By applying psychological principles, fraud examiners gain deeper insight into motives, detect deception through behavior, conduct more effective interviews, and build stronger preventive systems. In short, psychology transforms fraud investigation from a technical exercise into a comprehensive human-centered practice that gets to the root of misconduct. Hence, fighting fraud requires not just stronger laws and technologies but a deeper awareness of the human mind that drives deception.